A Procedure-focused Approach to Values and Environment

The discipline Environmental Ethics, as a branch of Applied Philosophy, was created around the 1960s, with the goal of using philosophy and its methods to contribute practically somehow to environmental management and protection, and to the other disciplines and wider community involved in these endeavors.1 Traditional environmental ethics, i.e. those works produced by the field roughly between the 1960s to 2010s, approached this practical goal by focusing on questions about the nature of value. Traditional environmental ethics has failed to fulfill its practical aim— it has failed to influence environmental norms and policies. (Heath, Light, Minteer et al. 2004) In this essay, I would like to elucidate the causes for this failure, by summarizing two distinct criticisms of the metaethical approach to value inquiry by (Heath) and (Minteer et al. 2004) respectively. After this diagnosis, I would like to explore a potential cure: a more procedurally-focused approach to value inquiry, which seems to be more immediately implementable and easily complied with. This will perhaps allow environmental ethics to produce the practical contributions for which it was created in the first place.

1. Expansionism

There was one specific question as to the nature of value, that was most defining of traditional environmental philosophy, and distinguished it from other applied philosophies: Whether only humans possessed intrinsic value, and anything nonhuman could only possess instrumental value, insofar as it furthered human interests. The position answering in the affirmative to this question was called Anthropocentrism.2 If there are things besides humans that have intrinsic value, they would be valuable independently of their instrumental value to humans. Things that have intrinsic value are to be considered for their own sakes; they have moral status and count as ethical subjects. (Gjerris) As to which entities should count as ethical subjects, substantive positions lie on a spectrum, ranging from humans-only to basically everything e.g. a 'cosmic' ethics.3 There are, however, four dominant positions: Anthropocentrism claims that only humans count as ethical subjects, as mentioned above in different terms. Sentientism claims that only sentient beings count as ethical subjects. Biocentrism claims that all living things, including non-sentient organisms like plants, count as ethical subjects. Importantly, for biocentrists and the two preceding positions, it is individual organisms that have moral status. This contrasts with the last position, ecocentrism, which claims that entire ecosystems count as ethical subjects. The ecocentric view may for example prioritize a species over its specimens, and also thinks non-living components matter, e.g. soil and minerals.4 The last three positions are Non-Anthropocentric (where Anthropocentrism is defined as human-interests-centric rather than human-valuation-centric, see footnote 2). There were two main motivations for Non-Anthropocentrism. The first was a fear of a human 'chauvinism'. (Heath 11, Light 2002 & 2003) It seemed arbitrary and unjustified to prioritize the interests of humans over everything else. So it was thought that the sphere of moral concern, of ethical subjects, should be expanded to include non-human things. Proponents of expansionism differed on which non-human things should be included as ethical subjects, as seen above. But they were nonetheless motivated by this same worry. The other motivation for Non-Anthropocentrism was the prevalent worry among traditional environmental ethicists that an anthropocentric value system would end up justifying acts and policies that would destroy the environment.5 At the very least, it wouldn't provide moral justification for all the environmentally protective norms and policies deemed necessary by the environmental sciences and wider environmental protection community. Proponents of this worry thought that only a non-anthropocentric value conception could provide justification with comprehensive coverage. For these two reasons among others, Non-Anthropocentrism became the dominant position in traditional environmental ethics.

The argument for Non-Anthropocentrism most prevalent in traditional environmental ethics was the Expansionist Argument (Heath), due to the aforementioned prevalent worry of human chauvinism. In brief, the argument runs: For something to count as an ethical subject, it must possess property P. We think only entities of class X are ethical subjects, because they possess P. But upon further inquiry, we find out that entities of class Y also possess P. So we must also include Y as ethical subjects, on pain of self-contradiction otherwise. The argument applies regardless of what one chooses as criterion of an ethical subject and definitive of moral status. Say the criterion of ethical subjects is that they have an objective interest, that there is a real sense in which they can flourish or not. Then plants must be included as ethical subjects, since they flourish when getting all the nutrients they need to grow etc. Heath (2022) argues that the Expansionist argument runs into a dilemma: an absurd conclusion on the one hand, arbitrary boundary-setting on the other. To take the Expansionist argument to its ultimate logical conclusion requires us to include everything, the entire cosmos, as subjects for moral concern— an absurd conclusion. But to stop somewhere before this would mean setting an arbitrary limit on the logical chain of the argument. The arbitrariness of this boundary-setting, i.e. the lack of a principled way to determine the boundary, gives room for people to draw the boundary at their subjectively preferred place, according to their inclinations and biases. This is what gave rise to the diversity of positions and lack of convergence regarding the question of which entities to include as ethical subjects. According to Heath, this lack of metaethical convergence, caused by the Expansionist dilemma, is the main reason why traditional environmental ethics failed to contribute practically. Disagreement and controversy about what to value was so great among environmental ethicists, that the discipline as a whole could not unite to provide any actionable plan or endorse any particular policy over another.

2. A Principle-ist Approach

Does this mean we can solve the problem by finding a non-expansionist argument for Non-Anthropocentrism? By finding a tenable and decisive alternative argument that would guarantee convergence among environmental ethicists, who would in turn unite to endorse particular policies over others, thereby having practical impact on the environmental community? Not so fast— how exactly does one go from convergence among philosophers to practical impact on the wider environmental community and its policies? It it neither necessary nor obvious that wider practical impact should be the natural consequence of philosophical convergence. On the contrary, Minteer et al. argue, traditional environmental ethicists failed to have practical influence because they assumed this— they assumed that uncontroversial answers to the metaethical question of value would lead to practical effects such as changes in people's moral attitudes and behaviors.6 Besides the question of whether or not to reject anthropocentrism, other important debates also defined traditional environmental ethics.7 But these other debates were still metaethical, and seemed to presuppose that the main task of environmental ethics was to settle the nature of value. Minteer et al. (2004) called this the "Principle-ist Approach". Proponents of this approach find it necessary to begin by finding and defending certain first principles a priori.8 Only after having found and justified such first principles is it possible to deal with concrete cases and problems. Such concrete cases namely require the application of justified first principles to them in a 'top-down' fashion. So traditional environmental ethicists found it necessary to define the nature of value first and a priori, before such a conception of value could be applied to environmental problems. They assumed "that the enterprise of moral inquiry must be preoccupied with the identification of fixed principles, rules, and standards, and that, once these concepts and claims are secured, those specific environmental decisions and actions will flow logically from them.”9 10

There are a couple of problems with this approach. First of all, it focuses on a metaphysical question that has remained unanswered since Plato ('what is the good'), and hopes to answer it uncontroversially in time to be applied to Environmental Problems.11 This is rather unrealistic. Such a time-consuming approach isn't appropriate for solving the time-sensitive and urgent problems of the environment. Decades have passed, and philosophers still don't agree on the nature of value, and they won't be doing so anytime soon, in any case, not soon enough. Secondly, even supposing a true, uncontested conception of value were available to us, applying such a general principle to particular cases or circumstances is not straightforward matter.12 It takes case-sensitive and intelligent deliberation to figure out how a general principle applies to a particular situation, with all of its unique intricacies and configurations. "Universal agreement upon the abstract principle even if it existed would be of value only as a preliminary to cooperative undertaking of investigation and thoughtful planning; as a preparation, in other words, for systematic and consistent reflection."13 So the job of environmental ethicists would not be done once they'd found the first principles of value— they would do further work on how to apply these general principles to particular cases. But for environmental ethics' goal of being of practically useful, the most important problem with the Principle-ist approach is that it goes against actual moral practice and experience, so much so that it most probably cannot be implemented. To explain this problem, it is useful to first clarify an important implication of the Principle-ist approach. The Principle-ist approach tries to find and justify principles a priori. The principles resulting from such an approach are justified prior to any empirical circumstances and considerations thereof. In other words, such principles are justified regardless of empirical circumstances, that is, justified in all empirical circumstances. The existence of a framework of principles that applies universally is the claim of monism.14 Since it aims at an universally governing framework, the Principle-ist approach presupposes monism. Another way to see this is that pluralism, the negation of monism, precludes an a priori method, thereby precluding the Principle-ist approach. Pluralism is the claim that there is no framework that governs all cases: different cases are governed by different frameworks i.e. hierarchies of principles (values). The methodical implication of this is that we need to look at the case before we can find out which framework governs it. In other words, we cannot know before considering the empirical circumstances, i.e. we cannot know a priori, which framework is justified to apply. So on pluralism, the a priori Principle-ist approach is impossible— pluralism implies a posteriori context-sensitive deliberation.15 To summarize, Principle-ist approach presupposes monism, to make possible its a priori method and aim.16

The pragmatist philosopher John Dewey argued that moral monism and a priori deliberation go against actual experience, moral experience and moral practice. He began with the empirical observation that circumstances are greatly diverse, and that each and every circumstance is unique in its configurations. From this undeniable empirical uniqueness, Dewey infers a moral uniqueness: "[E]very moral situation is a unique situation having its own irreplaceable good".17 This inference is substantive and can be contested, but the rationale is that our moral experience is shaped and constrained by experience tout court. Given experiential pluralism, different factors are at play in each and every situation, to varying degrees, with different configurations of conflicts of interest, perspectives, principles, values, etc. This makes it very implausible that there is one moral framework governing them all; that the same hierarchy of principles or values applies to all possible situations. Moral pluralism is far more plausible given the empirical diversity and uniqueness of experience. In turn, our moral practices and methods must be well-suited to this pluralistic experience. Such pluralism-compatible methods do not include the Principle-ist approach, which as mentioned is precluded by pluralism. Consider that if moral monism is true, then we would never need to deliberate morally. In any and all situations, we would already have the moral answer, namely the universally valid moral framework. We need only consider implementation, i.e. how the general principles apply to the particular circumstance. It seems exceedingly implausible that we could in moral practice remove all need for ever considering the circumstances.18 "Since past experience shows that these unstable and indeterminate contexts often find us struggling to harmonize disparate rights, duties, goods, virtues, and the like – each of which competes for attention and influence in our moral judgments – the selection of any one of these [frameworks] for special emphasis before contextual analysis thwarts intelligent moral inquiry."19

Empirical studies confirm that most people adopt value pluralism in practice, and that they do not make moral deliberations in an a priori manner without regard for context. (Minteer et al. 1999, 2000, 2004) People do not take some moral framework for granted as universally applicable, and wonder only about how it should be applied. They consider alternative moral frameworks, and which ones they consider is usually determined by the situation— people usually begin by considering the concrete situation and context rather than the first principles. A context usually has associated norms and requirements, which generate a finite list of salient moral frameworks, principles and values for individuals to consider, evaluate and weigh against each other. People rarely assess alternatives in a context-independent, 'first-principles first' manner. In practice, people morally deliberate in a context-sensitive manner. The upshot of all this is that the Principle-ist approach, a context-independent approach, would result in very low compliance. Regardless of which moral framework is chosen, very few people would be willing to actually adhere to it in an a priori and universal manner, as this would mean always and completely disregarding the circumstances, which very few people are willing to do.20 So even if environmental ethicists came to agree on Non-Anthropocentric value, this cannot be expected to have practical impact on people or policies.21 The traditional environmental ethicists' assumption, that convergence in metaethical value would lead to practical impact, is wrong. To achieve practical impact, it is not sufficient that philosophers find and agree on the nature of value.

3. Value Inquiry Procedures

The previous section has showed us that philosophical convergence on the nature of value is will not change people's moral deliberations in practice. Derivatively, it would have negligible practical effect on policies. But this does not mean that the question of value can be dispensed with altogether. The impossibility of value-neutrality in science is well defended in philosophy of science. (Douglas, Steele 2012) Empirical evidence shows the pervasiveness and omnipresence of values. Empirical analyses like risk assessments and cost-benefit analyses are 'framed' by value assumptions, and different framings yield dramatically different results.22 Climate change projection models are value-laden in that they inevitably prioritize the accuracy of some variables over others (Parker, Parker & Winsberg), or certain value intervals within a variable over others. (Garner & Keller) To consider climate change a problem at all presupposes a human-interests-centric value system,23 or at least a system that values specifically those species and organisms that would be threatened by temperature increase. For there are species and ecosystem types that would thrive upon an increase in average global temperature, and climate change is not a problem at all seen from their perspective. To consider current climate change a problem seems to presuppose time-scales relevant to humans.24 On geological timescales, dramatic changes in both climate and geology have been a natural matter of course, not some unique catastrophe in the history of the Earth. In short, it is impossible to proceed value-neutrally in anything. Even if we do not make our own values explicit to ourselves, we presuppose them in the way we think, act and deliberate. It doesn't help to just close our eyes to them, they will govern our actions and decisions regardless. So we must clarify our values, if we want our efforts at solving environmental problems to be deliberate, and the outcomes to be as intended (with a margin of imprecision and uncertainty of course, but not so far besides our target as to be completely unintentional). Clarifying our values is also important to make sure our norms, policies and decisions are internally consistent, which is desirable, since inconsistency would mean that we sometimes pursued contradicting, counteracting goals, thereby reducing overall effectiveness.

Given the necessity of value inquiry, how do we proceed? The traditional approach to environmental value inquiry has proven unfruitful. It insisted on finding some finally valid values before proceeding with any practical work. But this is not the only possible approach to value inquiry. Instead of working on finding final values, we can adopt some acceptable preliminary values, and work on devising a valid procedure for incremental value learning, updating and improvement. For the rest of this essay, I would like to explore some procedurally-focused approaches to environmental ethics. Let us begin with the Dewey-inspired approach proposed by Minteer et al. (2004), since we used their criticism of the Principle-ist approach to explain why it failed. They propose a contextualist approach opposite to the principle-ist approach. Instead of beginning with first principles and then applying them to a particular situation, we begin with the concrete situation, and reason towards the relevant moral principles. As mentioned before, a context of a situation tends to have associated norms and principles, and these are the principles that are considered, so that only those principles that are relevant to and associated with the context that are considered. This contextualist approach satisfies people's need to practice case-by-case deliberation and context-sensitivity. Besides beginning with the situation to arrive at relevant principles, they suggest we focus on situations with conflicts of interest between environmental and social concerns. This is to prioritize our deliberative efforts efficiently. Where there are no conflicts of interest, we should obviously go right ahead and choose win-win solutions. It is where there are conflicts that we need to find out what to prioritize i.e. what our values are. In these cases of conflict, we must apply active and intelligent deliberation to adjudicate between the conflicting values and interests. You could say that this contextualist pragmatic approach to value inquiry takes a problem-first rather than a principles-first approach. This approach fits well with our context-sensitive moral phenomenology, so it can be expected to be practically implementable and complied with. Besides, it narrows down the number of salient moral principles to a manageable number and efficiently prioritizes our deliberative efforts.

4. Public Deliberation

We gave up trying to find the correct answer (as to the nature of value) right away, and opted instead to find a procedure for producing answers. But the procedure we seek must produce good answers. What kind of procedural features would enable this? Dewey thinks that deliberative processes (which include our value inquiry procedure) should always be undertaken by everyone— deliberation should be accessible to all and contributed to by all. Dewey is a proponent of public deliberation and deliberative democracy for epistemic reasons. He believes experience and the sharing of experience to be the only means to attaining knowledge.25 So knowledge requires public deliberation, which is the political implementation of experience sharing. Universal accessibility and contribution to deliberation promotes experience sharing and the elimination of false ideas.26 Talisse (2004, 2009) argued that deliberative democracy was epistemically desirable because it enables a learning process. Citizens may be incompetent right now, but they can become competent via public deliberation. This fits nicely with our aim of finding an alternative to the Principle-ist approach. Instead of trying to find the correct conceptions of value right now, we can trust in public deliberation as a process which will generate incrementally improving conceptions of value. Deliberative democracy may also be especially epistemically well-suited to areas like environmental ethics, where there is a persistent lack of expert convergence (here, about the nature of value). Peter (2016) argues that when expert knowledge cannot be relied upon, for example when there is persistent, reasonable disagreement among experts, and there is persistent, reasonable disagreement among laymen, the best we can do epistemically is to decide by whole citizenry majority vote.

There may be other reasons, besides epistemic ones, why our value deliberation procedure should be public. Specifically when it comes to matters of value rather than fact, public deliberation can be considered the criterion of legitimacy. Without getting too deep into details, or adopting any substantive position in epistemology, philosophy of science, ethics or any other discipline that has addressed the is-ought distinction, it can be accurately said that claims about fact and claims about value differ in what legitimizes them. Factual claims can be legitimate in many ways, e.g. by being considered true, or having highest probability of being true, or being a justified belief because the procedure that lead to that belief was epistemically virtuous etc. Whichever specification is adopted, factual legitimacy is evaluated with reference to an objective standard of some sort. Objective is variously defined in the literature, but at the very least it means not subjectively biased, i.e. independent of individuals' subjective beliefs, preferences or experience.27 Thus, an objective standard is what judges whether factual claims are legitimate. By contrast, there is no objective standard to evaluate and legitimize value claims. This is precisely why value claims call for deliberation, which function is to figure things out in cases where there are no clear or correct answers, cases of indeterminacy, uncertainty, unpredictability, i.e. cases without an objective standard for evaluation. In such cases, values and preferences powerfully regulate how one proceeds. "[W]e do not deliberate to "track the truth", but rather to decide how to act when there is no "truth" of the matter (…) often because what is at issue is a matter of value and purpose, not simply facts."28 And since values concern what people prefer, what they are willing to do, what they are willing to give up etc., value deliberations need to be public and inclusive to gain people's genuine consent, support and willingness to comply. These are what give values their legitimacy and authoritative force.

There is no prima facie reason why inclusive public deliberation, as a criterion of value legitimacy, should not apply to values in nature and environment as well. Let us see how public deliberation, as a legitimizing criterion, could play out in environmental ethics. I will use Habermas' specification of political legitimacy, for illustrative and not substantive reasons. According to Habermas, a policy is only politically legitimate insofar as all parties affected by the policy were allowed to participate in deliberations about it, and consensus was reached without coercion, which requires deliberations be impartial and rational. (Elster) So, only those conceptions of natural and environmental values are legitimate, that are the result of a consensus reached by a rational and impartial deliberative process, in which all parties affected by the values participated. The environmental values resulting from such a deliberation process can thus be considered legitimate. Or at least, they are legitimate until further— it may be that the current consensus is not optimal, and if affected parties knew better they would demand renegotiation. But this is not a problem: legitimacy is maintained by the possibility of renegotiation, i.e. of beginning anew the inclusive deliberative process. Current policies remain legitimate so long as affected parties still uncoercedly consent to current consensus. In the context of our value inquiry procedure, which aims at incrementally improving (ergo changing) our conceptions of value, we can use inclusive public deliberation to periodically legitimize the latest, most updated conceptions of value (which are then legitimate until further). This criterion of legitimacy can also be a way for us to pick out our the preliminary values, the starting values to begin our procedure of incremental value learning and improvement.

There is an important problem with applying a legitimacy criterion based in inclusive deliberation to specifically environmental values: Non-human entities cannot participate in the deliberations themselves, yet they are undoubtedly parties affected by the values in question. But I do not see this problem as decisively undermining the possibility of public deliberation as one potential solution to environmental value inquiry. On the contrary, I see it a beginning, a puzzle to launch inquiry in salient directions. An example question to pursue from this point is whether it might not be possible to incorporate non-human affected parties into the deliberations after all. These non-human affected parties need perhaps not ‘speak’ themselves— perhaps the notion of 'trustee' (Ashford & Mulgan) could be incorporated fruitfully, with people representing non-humans and negotiating on their behalf. Perhaps it is the apt role of philosophers to be such representatives of non-human entities, to try and see things from the ‘wolf’s perspective’.29 Of course, as we saw, merely imposing values as first principles on the public won't have practical effect. So philosophers would have to communicate these alternative perspectives persuasively, for example by facilitating informal deliberative forums, where people can practice deliberating from these various perspectives and work through the various arguments themselves. Such informal deliberative forums have proven effective in making people's preferences less erratic and in cultivating 'public will' i.e. increased consensus on values.30

5. Final Remarks

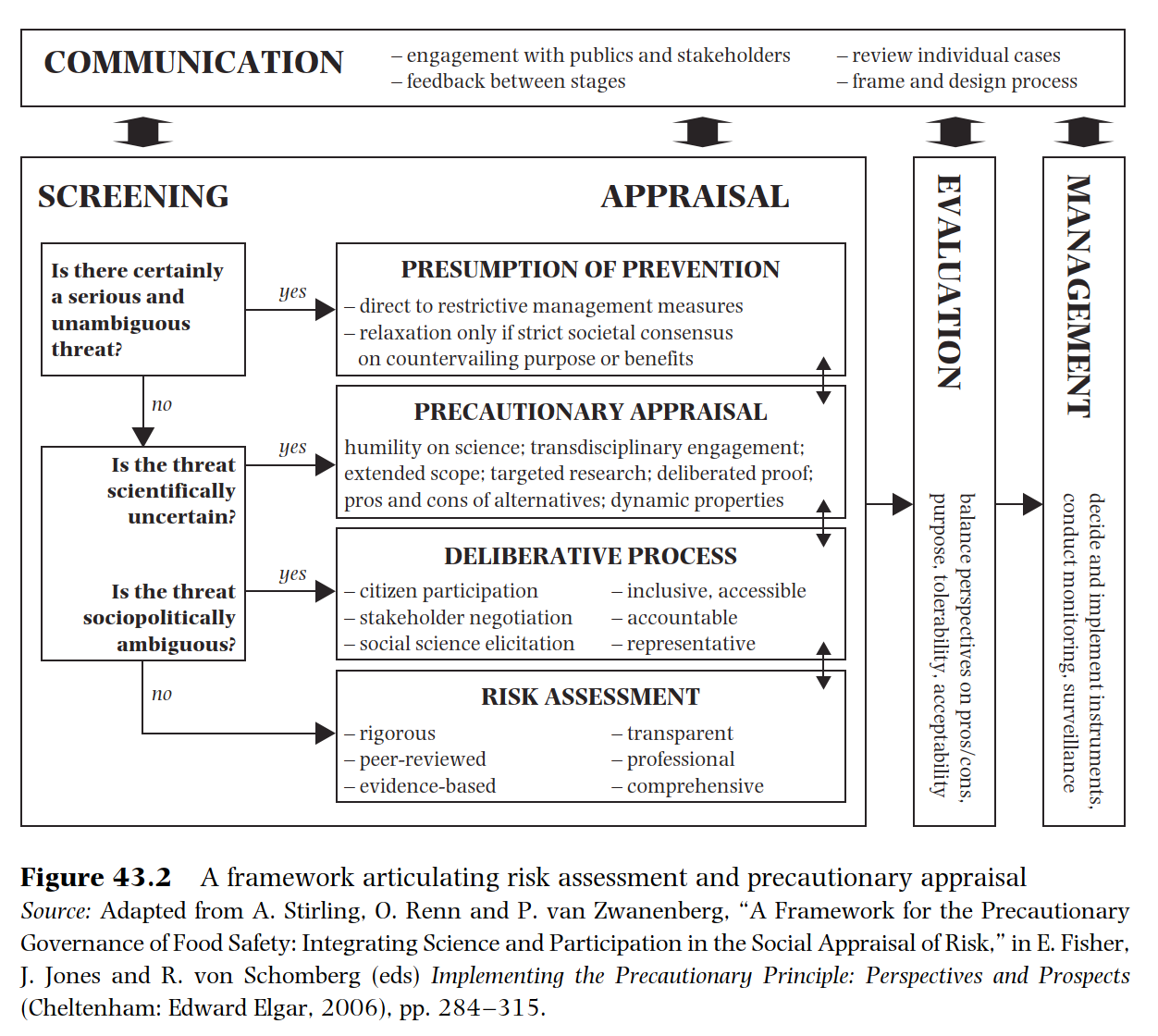

It may seem like the suggested alternative procedural approach, and its discussed features, remain very theoretical, with low potential for practical impact. But there is precedent for their practical implementation, for example the Stakeholder-Deliberations Framework (Stirling et al. 2006, see figure 43.2). It is an iterative procedure for implementing the value of precaution, with the explicit rationale that it is best realized as a process rather than “decision rule.” The framework illustrates our legitimacy criterion by requiring all stakeholders i.e. potentially affected parties be included in the process. Where there is doubt about values (‘Is the threat sociopolitically ambiguous?’), it calls for public deliberation. Where there is doubt about facts (‘Is the threat scientifically uncertain?’), it calls for more social i.e. inclusive learning, illustrating our epistemic considerations. This is just one example of a procedure for value inquiry, and decision-making more broadly, that can be immediately applied fruitfully to environment. Other lines of inquiry that seem particularly relevant to environment are decision theory, applied decision sciences and heuristics, specifically on the topic of decision-making under deep uncertainty. (Bradley & Steele, Hansson, Sprenger) A procedurally-focused approach will have its own problems to be sure. Nonetheless, a simple shift from looking for good answers to looking for good procedures will generate prescriptions more immediately implementable and willingly complied with, thus helping environmental ethics get out of its impractical rut.

References

Ashford, Elizabeth and Tim Mulgan. "Contractualism." The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2018.

Bradley, Richard, and Steele, Katie. “Making Climate Decisions.” Philosophy Compass, vol. 10, no. 11, 2015, pp. 799–810, https://doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12259.

Dewey, John. "Creative Democracy.” The Essential Dewey Volume 1, edited by I.A. Hickmann and T.M. Alexander. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998 (orig. 1939), pp. 340–343.

Dewey, John. "Ethics." The Later Works of John Dewey Volume 7, edited by Jo Ann Boydston. University of Southern Illinois Press, Carbondale, 1989 (orig. 1932).

Dewey, John. Reconstruction in Philosophy. Beacon Press, Boston, 1957 (orig. 1920).

Douglas, Heather. Science, Policy, and the Value-Free Ideal. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2009.

Elster, Jon. "The market and the forum: three varieties of political theory." Deliberative Democracy: Essays on Reason and Politics, edited by Bohman, James, et al. The MIT Press, 1997. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.001.0001.

Fox, Warwick. Toward a Transpersonal Ecology. Albany: SUNY Press, 1995.

Garner, Gregory G., and Klaus Keller. “When Tails Wag the Decision: The Role of Distributional Tails on Climate Impacts on Decision-Relevant Time-Scales.” arXiv.org, 2017.

Gjerris, Mickey. "What about Nature." The good, the right & the fair : an introduction to ethics, edited by Gjerris, Juul Nielsen, M. E., & Sandøe, P. College Publications, 2013, pp. 54-73.

Hansson, Sven O. “Decision Making Under Great Uncertainty.” Philosophy of the Social Sciences, vol. 26, no. 3, 1996, pp. 369–86, https://doi.org/10.1177/004839319602600304.

Heath, Joseph. “The Failure of Traditional Environmental Philosophy.” Res Publica (Liverpool, England), vol. 28, no. 1, 2022, pp. 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-021-09520-5.

Helgeson, Casey. “Structuring Decisions Under Deep Uncertainty.” Topoi, vol. 39, no. 2, 2020, pp. 257–69, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-018-9584-y.

Kempton, Willett, et al. Environmental Values in American Culture. The MIT Press, 1997.

Kolbert, Elizabeth. The Sixth Extinction. New York: Henry Holt, 2014.

Light, Andrew. “Contemporary Environmental Ethics From Metaethics to Public Philosophy.” Metaphilosophy, vol. 33, no. 4, 2002, pp. 426–49, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9973.00238.

Longino, Helen. "Values and Objectivity." Science as Social Knowledge. Princeton University Press, 1990, pp. 62‐82.

McAfee, Noëlle. "Public Philosophy and Deliberative Practices." A companion to public philosophy, edited by McHugh, Olasov, I., & McIntyre, L. C. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2022, pp. 134-142.

Minteer, Ben, and Manning, Robert. “Convergence in Environmental Values: An Empirical and Conceptual Defense.” Ethics, Place and Environment, vol. 3, no. 1, 2000, pp. 47–60, https://doi.org/10.1080/136687900110756.

Minteer, Ben, and Manning, Robert. "Pragmatism in Environmental Ethics: Democracy, Pluralism, and the Management of Nature." Environmental Ethics, 21, 1999, 191–207.

Minteer, Ben A., et al. “Environmental Ethics Beyond Principle? The Case for a Pragmatic Contextualism.” Journal of Agricultural & Environmental Ethics, vol. 17, no. 2, 2004, pp. 131–56, https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JAGE.0000017392.71870.1f.

Parker, Wendy. “Values and Uncertainties in Climate Prediction, Revisited.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, Part A, vol. 46, 2014, pp. 24–30, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2013.11.003.

Parker, Wendy S., and Eric Winsberg. “Values and Evidence: How Models Make a Difference.” European Journal for Philosophy of Science, vol. 8, no. 1, 2018, pp. 125–42, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13194-017-0180-6.

Peter, Fabienne. "The Epistemology of Deliberative Democracy." A companion to Applied Philosophy, edited by Lippert-Rasmussen, Brownlee, K., & Coady, D. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2017, pp. 76-88.

Peter, Fabienne. “The Epistemic Circumstances of Democracy.” The Epistemic Life of Groups, edited by M. Fricker and M. Brady. Oxford University Press, 2016.

Sprenger, Jan. “Environmental Risk Analysis: Robustness Is Essential for Precaution.” Philosophy of Science, vol. 79, no. 5, 2012, pp. 881–92, https://doi.org/10.1086/667873.

Steele, Katie. “The Scientist Qua Policy Advisor Makes Value Judgments.” Philosophy of Science, vol. 79, no. 5, 2012, pp. 893–904, https://doi.org/10.1086/667842.

Steele, Katie, and H. Orri Stefánsson. “Decision Theory.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2015.

Stirling, Andy. "The Precautionary Principle." A Companion to the Philosophy of Technology, edited by Olsen, Pedersen, S. A., & Hendricks, V. F. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2009, pp. 248-262.

Stirling, Andy et al. “A Framework for the Precautionary Governance of Food Safety: Integrating Science and Participation in the Social Appraisal of Risk.” Implementing the Precautionary Principle: Perspectives and Prospects, edited by E. Fisher, J. Jones and R. von Schomberg (eds). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2006, pp. 284–315.

Talisse, Robert B. Democracy and Moral Conflict. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Talisse, Robert B. “Does Public Ignorance Defeat Deliberative Democracy?” Critical Review (New York, N.Y.), vol. 16, no. 4, 2004, pp. 455–63, https://doi.org/10.1080/08913810408443619.

Heath 2↩︎

Heath (2022) clarified that Anthropocentrism need not mean human-centric interests, but could also mean human-centric valuation. A certain conception of value was anthropocentric, if it adopted a human perspective, a human way of valuing things. Importantly, this implies the possibility of humans valuing certain things intrinsically, i.e. for their own sakes and not for their instrumental value for human interests, but that this would still be an anthropocentric value, since those things would be intrinsically valuable by human standards. But let us set aside this expanded notion, since the defining question of traditional environmental ethics was about human-centric interests.↩︎

Fox 162–179↩︎

Heath 7 footnote 5↩︎

Minteer et al. 2004, 136↩︎

Minteer et al. 2004, 135-136↩︎

Light (2002) summarizes the traditional literature by retracing the four main disagreements of traditional environmental ethics. The first debate was the aforementioned Anthropocentric versus Non-Anthropocentric value debate. The second debate, that of individualism versus holism, concerned whether the primary subject of environmental-ethical concern should be individual organisms or entire systems. Individual organisms can be sentient or not, for example on Sentientism and Biocentrism respectively. And the aforementioned Ecocentrism is an example of Holism. Holism became the dominant position in Environmental Ethics, for the same reasons as for Non-Anthropocentrism. i.e. it was thought that holism could better justify the norms and policies of the environmental sciences (such as ecology) and wider environmental community. The third debate, that of subjectivism versus objectivism, concerned whether value is subjective or objective. This debate has not resulted in any dominant position. The last big debate, that of ethical monism versus pluralism, concerned whether all the different cases relevant to environmental ethics can and should be dealt with by a single ethical system (be it one value or principle or one set of values or principles), applicable to all cases. Pluralism claims that we need multiple systems, and that different systems apply depending on the case. This debate has not resulted in any dominant position either, but some of its contributions have ended up challenging the dogmatic status of Non-Anthropocentrism.↩︎

In the case of traditional environmental ethics, the principles are conceptions of value, so principles and conceptions of value will be used interchangeably.↩︎

Minteer et al. 2004, 154↩︎

Light (2002) notes that the Principle-ist approach was dominant in environmental ethics, but not in other areas of applied philosophy e.g. bioethics, because the other areas mostly deal with interactions and conflicts between humans only, which our existing ethical theories were well equipped to handle. As such, the first principles for ethics between humans were already found or sufficiently argued for by these traditional ethical theories, and it was possible to go straight to their application to cases. By contrast, traditional ethical theories weren't equipped to handle interaction and conflicts with non-human entities, which are omnipresent in environmental matters.↩︎

Heath 14↩︎

Minteer et al. 2004, 137↩︎

Dewey 1989, 178↩︎

See footnote 7 for brief definition of monism and pluralism. A moral framework can consist of one or many principles. If there are many principles, the framework must provide a rank-ordering of them i.e. a hierarchy of priority. On monism, there is only one such framework that is valid, i.e. one hierarchy of priority applies universally to all cases. ↩︎

Minteer et al. 2004, 138↩︎

But monism need not presuppose or imply the Principle-ist. Even if there existed only one valid moral framework that applied universally and eternally, it is possible that our approach to discovering this fact was a posteriori rather than a priori, e.g. that we arrived at the conclusion that one moral framework governs all cases by empirical accumulation.↩︎

Dewey 1957, 163↩︎

Note that I am not here making the metaethical assertion that pluralism is true and monism is false. I merely claim that monism would not be effective in practice, since few people would actually adopt and implement it.↩︎

Minteer et al. 2004, 138↩︎

It can be argued that current patterns of moral deliberation need not continue forever, that people may be conditioned towards a less context-sensitive deliberative approach. I concede this possibility, and but set it aside for a couple of reasons. First, the probability of this possibility must be practically significant, and I see the burden of proof for this claim as lying with its proponents. Second, such behavioral change takes a long time, and environmental problems are urgent. Third, and not unrelated to the second reason, it makes strategic sense to me to choose methods and solutions based on what is already the case, rather than what could be.↩︎

Empirical surveys even show that people are generally more motivated to protect nature and the environment for anthropocentric reasons and values than non-anthropocentric ones. (Kempton et al., Minteer et al. 1999)↩︎

Stirling 249↩︎

Heath 13↩︎

Heath 11, Kolbert↩︎

Importantly, Dewey's argument for Deliberative Democracy is noninstrumental— he is not arguing that it is epistemically preferable because it leads to better outcomes, but because it is an epistemically virtuous procedure.↩︎

Dewey 1939, 343↩︎

Longino 1990. So defined, an objective standard need not be completely independent of any form of consensus whatsoever, e.g. Longino understands objectivity as a way of perceiving and interpreting perceptions that seems plausible and rational to most, if not all, people. Objectivity so defined is a species of consensus.↩︎

McAfee 136↩︎

Heath 9. Heath also mentions the concern of why non-human perspectives should concern humans at all. I do not make any substantive claims about that, and merely wish to illustrate the sorts of questions that environmental ethics can work on in this direction. ↩︎

McAfee 140↩︎